Bringing the A3 to Life: A Resource to Drive Evidence-based Action

July 26, 2022

The Population Council GIRL Center’s mission has always been data-driven. The programs we’ve built and the policies we’ve helped craft are guided by advanced demographic analyses that allow decision-makers to target specific issues and ensure that resources are used effectively. Our latest innovation in using data for change is the Adolescent Atlas for Action (A3), a set of free online tools for exploring gaps in adolescent education, health, and well-being around the world.

For more insights on the launch of the A3, we asked Dr. Karen Austrian, Director of the GIRL Center, about her experience and perspectives on adolescent research and what the A3 can contribute. With 15 years of research experience with the Population Council focusing on empowering adolescents, Karen has been a champion of evidence-based policy action, especially in Africa.

GIRL Center (GC): Congratulations on the launch of the A3! In your first year of stepping into the role as Director of the GIRL Center, this seems like a major milestone for your first set of accomplishments.

Dr. Karen Austrian (KA): It’s has been a very exciting first year! The GIRL Center is working hard to champion evidence-based solutions for the challenges facing adolescents around the world today, and the A3 is an important step in our work of being a leading knowledge partner in this area of work.

GC: We heard from Thoai about the initial motivation behind the A3. In your role as the GIRL Center Director, you led the process of bringing the idea to life. What makes the A3 unique compared to other data-based resources?

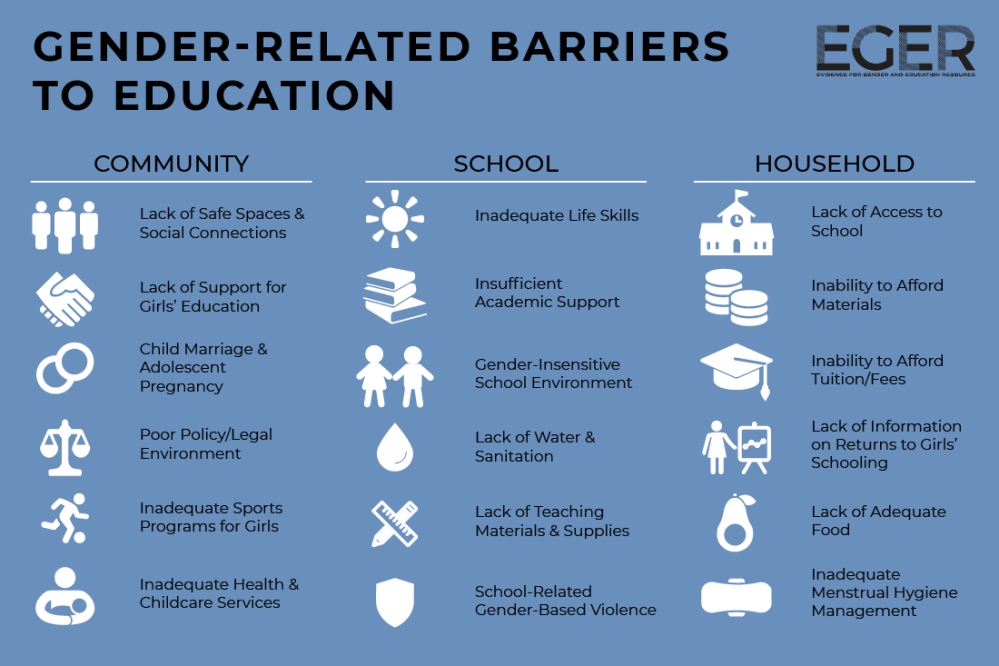

KA: First is that many of the interactive databases out there are based on descriptive, single indicators. The A3 has analytical work already done behind the scenes to reflect our thinking on how vulnerabilities facing adolescents are interlinked. We know from experience in working with adolescent girls that thinking one indicator at a time limits our ability to effectively support girls. Because in real life, the wide range of indicators constantly interact. For instance, gender norms in a girl’s community impacts her education, which in turn affects her employment. Or another example is how a girl’s economic situation often shapes the decisions she makes about her sexual health, relationships, etc. The A3 aims to paint a more realistic, holistic picture of adolescent lives, by presenting the interlinkages of indicators.

“The A3 paints a more realistic, holistic picture of adolescent lives, by presenting the interlinkages of indicators.”

Secondly, the data in the A3 goes beyond national level data and dives into subnational level data. National level data masks where pockets of extreme marginalization and vulnerabilities exist. Relying on national averages alone may also overlook geographic disparities within a country. There are still limits to subnational data that is available but this will continue to be a critical area of work in progress.

GC: Before taking on the role as Director of the GIRL Center, you worked at the Population Council for 15 years as a researcher focusing on adolescent girls. From a researcher’s perspective, how can A3 strengthen or contribute to ensuring that data drives policies and actions for adolescents?

“a tool that can be utilized to not only extend the partnership between research and policy, but also to strengthen capacity building”

KA: From my experience, the key to getting policy makers to utilize research at the country or local level is to build a relationship with them and act as a knowledge partner. Being available to share key information more broadly – rather than focusing on sharing specific research studies or journal articles – with the data that exists has been important. Furthermore, presenting evidence that is relevant to the context in a country or region is central to connecting research to policy in a holistic way. Population Council Kenya researchers, for example, have participated in the adolescent health strategy meetings of the Presidential Policy and Strategy Unit (PASU) to advise on indicators for the strategy.

The A3 makes our role as a knowledge partner easier and aids decision makers. Before, we had to undertake additional studies to apply our core research to specific contexts to connect the dots. Now with the A3, contextualized evidence at the national and subnational levels and a snapshot of how prominent factors in a community are interrelated are all available online. For policy makers and government officials, the A3 can make evidence-informed decision-making less daunting. At the same time, the A3 will be a tool that can be utilized to not only extend the partnership between research and policy, but also to strengthen capacity building.

GC: What is your vision for the A3 over the next five years? How does this fit into your vision for the GIRL Center’s next five years?

KA: I hope the A3 will be a living resource that continues to grow and be responsive to the evolving needs of users. I envision the A3 to put data and evidence into the hands of drivers of change and innovations, ranging from policy makers to program designers and to adolescents themselves.

Similarly, my vision for the Center is to become the go-to place for data and evidence-informed insights on adolescent girls. Having the A3 is key for the Center’s belief that adolescent girls are at the nexus of the world’s pressing issues, as the platform can help bring together people from different countries, sectors, and roles in helping adolescent girls through evidence-based solutions. The A3 can be a helpful resource, guide, or even a conversation starter that draws on the GIRL Center and Population Council’s multi-decade history of knowledge and expertise in this field.

“I envision the A3 to put data and evidence into the hands of drivers of change and innovations, ranging from policy makers to program designers and to adolescents themselves.”

GC: Thank you for sharing your perspectives, Karen!

We encourage all our readers to visit the new Adolescent Atlas for Action (A3), and share it with colleagues working on adolescent wellbeing. Reach out to the GIRL Center at a3@popcouncil.org to follow up or ask additional questions.