Promoting Opportunities for Adolescent Girls in the Sahel Region through Evidence-Informed Programming

March 20, 2023

This A3 Insights describes key elements of the Population Council’s work on the Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend initiative (SWEDD), which aims to reduce risks and promote opportunities for adolescent girls and young women. The work described in the blog post is executed through UNFPA, the organization tasked with overseeing SWEDD activities and providing technical assistance to SWEDD countries in collaboration with its technical assistance partners (including Population Council). Subsequent posts will cover lessons learned, insights generated, and other related themes from the Council’s SWEDD project. This piece was authored by Miriam Temin (Project Co-Director) primarily, and Anne-Caroline Midy (Project Coordinator).

Unique challenges facing adolescent girls and young women in the Sahel region

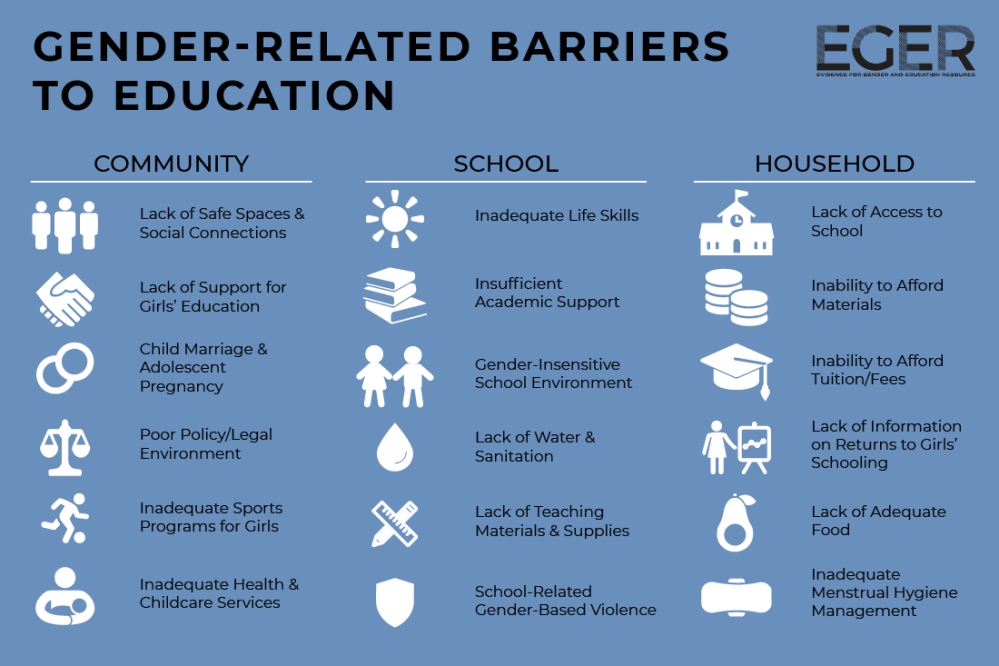

During the dynamic life phase of adolescence, many girls in West Africa’s Sahel region grapple with multiple threats to their health and well-being, undermining their potential to access their rights and thrive as adults. Many of these challenges are complex and multi-factorial, reflecting intersecting, long-standing forces and systemic issues. Indeed, the region includes countries with some of the highest rates of poverty, food insecurity, conflict, and population displacement in the world.

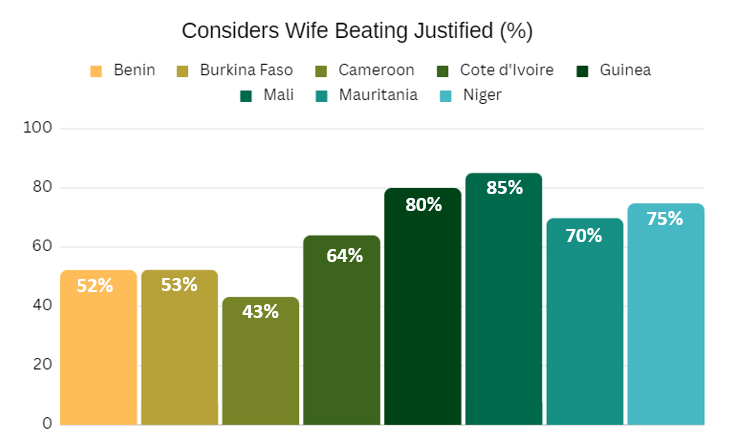

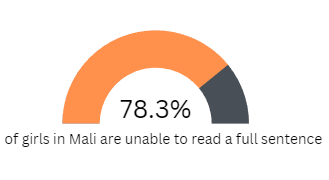

The adolescent indicators dashboard from the GIRL Center’s Adolescent Atlas for Action (A3) provides data for a closer look at various threats in Sahel countries. Using data from nationally representative surveys in Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroun, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger, the adolescent indicators dashboard makes a strong case for urgent action for girls and young women in the Sahel.

For example, the dashboard shows that in Mali, Guinea, and Cote d’Ivoire, over 20% of adolescent girls have given birth at least once, while in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, that statistic exceeds 30%. 61% of adolescent girls were married or living in union in Niger. In Mali and Guinea, over 60% of adolescent girls consider wife beating justified. Strikingly, the dashboard also highlights that Niger, Guinea, and Mali are among the countries with the highest prevalence of illiteracy in the world, with the vast majority of adolescent girls being unable to read a whole sentence.

Supporting the use of evidence and resources by government and implementing partners

While the Sahel historically has been underserved by overseas development assistance, the current moment provides exciting opportunities as more bi- and multilateral organizations make the Sahel region (and more specifically, French West Africa [FWA]) a priority. Large investments offer the possibility of supporting governments and civil society, growing capacity, and strengthening the evidence base to reduce risks and enhance opportunities for girls.

Starting in early 2020, the Population Council stepped into this landscape as part of the World Bank’s Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend (SWEDD) Initiative, building on our existing and recent portfolio of FWA research and deep adolescent girl expertise.

Funded by the World Bank to the tune of over US$700 million[1] for the period 2014-24, SWEDD’s overall aim is to “increase women and adolescent girls’ empowerment and their access to quality reproductive, child and maternal health services in selected areas of the participating countries” by reducing child marriage, early pregnancy, and girls’ school leaving, inter alia.

SWEDD is a regional activity, expanding from an original six to the current set of nine countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroun, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Tchad).[2] The governments of these countries lead the initiative, with participation from multiple ministries and implementing partners. Taken together, the range of SWEDD activities was established to position these countries to reap a demographic dividend, whereby rapid economic growth is possible under the right conditions when the size of the young, dependent population shrinks relative to the size of the population of working adults.

Within SWEDD, the Council uses evidence and our capacity, relationships, and tools and other program resources to support activities that target adolescent girls and young women. We do so by strengthening national and sub-national capacity to make evidence-informed use of SWEDD resources based on our large body of evidence on what works and what doesn’t work to reach marginalized adolescent girls and reduce their risks. We aim to increase the quality of SWEDD programming through process documentation; training for managers and implementers on key skill sets; implementation science; regional capacity strengthening workshops, and other activities that aim to promote the use of evidence for action.

For instance, we drew upon effective Council programs to create a second-generation curriculum for mentors in SWEDD’s safe spaces, as well as a bespoke safe spaces minimum standards guide. We developed instructional materials to guide implementers on topics such as non-formal literacy training and operating community-based girl groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. Providing focused technical assistance and strengthening capacity to improve monitoring, evaluation, and learning functions is also a priority area that leverages the Council’s expertise and programmatic resources.

Addressing gendered risks through a multi-sectoral and multi-level approach

SWEDD is uniquely designed to take on the social and structural drivers of gendered risks through a package of programming that is multi-sectoral and works at multiple levels. Its interventions address individuals, communities, local government representatives, and policymakers through the health sector, schools, communities, and demographic researchers. This reflects the importance of socio-ecological approaches to sustainably reduce girls’ risks, based on evidence from the Council and elsewhere.

Recognizing that individuals underlie the summary statistics shared above, the bulk of the Council’s inputs and the largest SWEDD components directly engage community members and adolescent girls and young women (AGYW). Through life skills training in mentor-led safe spaces (espaces surs) groups in communities and schools, mentors aim to equip AGYW with knowledge, skills, and assets to empower them and enable them to navigate risk. In an effort to reap the proven benefits of gender-transformative programming, we support partners to create synergies between safe spaces and SWEDD clubs for husbands and future husbands (clubs des maris et des futurs maris).

Looking ahead: Using early SWEDD lessons to sustain and scale country-owned action

As country-level actors implement the second phase of SWEDD and plans for the third phase take shape, Population Council, along with other technical partners, has a continuing role in promoting evidence, good practice, and learning. Given SWEDD’s large size and ongoing expansion, it will be important to build upon the essential enablers of program success to continue to sustain and scale country-owned action. The multi-sectoral and multi-leveled approach offers countries the opportunity to bring evidence-informed practice together in intentionally selected geographies or ‘hot spots’. Governments in participating countries lead the charge, demonstrating their commitment to SWEDD goals through the involvement of multiple ministries and laying a foundation for sustainability. Furthermore, ownership of SWEDD extends to communities and local opinion leaders including through the active participation of religious leaders in many countries, accounting for the strong influence of community norms in influencing the impact of adolescent girl programming.

At this stage, it is equally vital that lessons from the early days of SWEDD are available and informing expansion, leveraging the regional aspect of the initiative. The Council continues to advance this objective by facilitating cross-learning between country-level stakeholders, documenting and disseminating lessons on ‘safe spaces’ implementation, and using implementation science to identify and expand effective practices that will be feasible and sustainable in SWEDD settings.

To learn more about the Council’s role in the World Bank’s SWEDD Initiative, click here.

This piece is also available in French.

[1] Figure up to date as of 10/20.

[2] SWEDD III is currently being planned for Senegal, Congo-Brazzaville, Togo, Gambia.