Roe v. Wade in the Global Context of Abortion Policies

October 21, 2022

This A3 Insights is published under our ‘Youth Perspectives’ series, where Population Council colleagues, fellows, interns, and partners under the age of 30 write a data-driven thought piece focused on their own interests and research areas.

This piece, authored by Tara Abularrage, GIRL Center Intern and MPH candidate at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health, centers the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade in the global landscape of abortion policies, outlines the implications of this decision on sexual and reproductive health and rights, and maps current abortion policy indicators across 113 LMICs using the A3 policy checklist.

On June 24, 2022, the United States Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, reversing decades of legal precedent. This makes the U.S. one of only four countries to remove protections for legal abortions in over 25 years. This attack on evidence-based policymaking and the rights of birthing people will have a broader impact on reproductive health, rights, and autonomy in the US and globally.

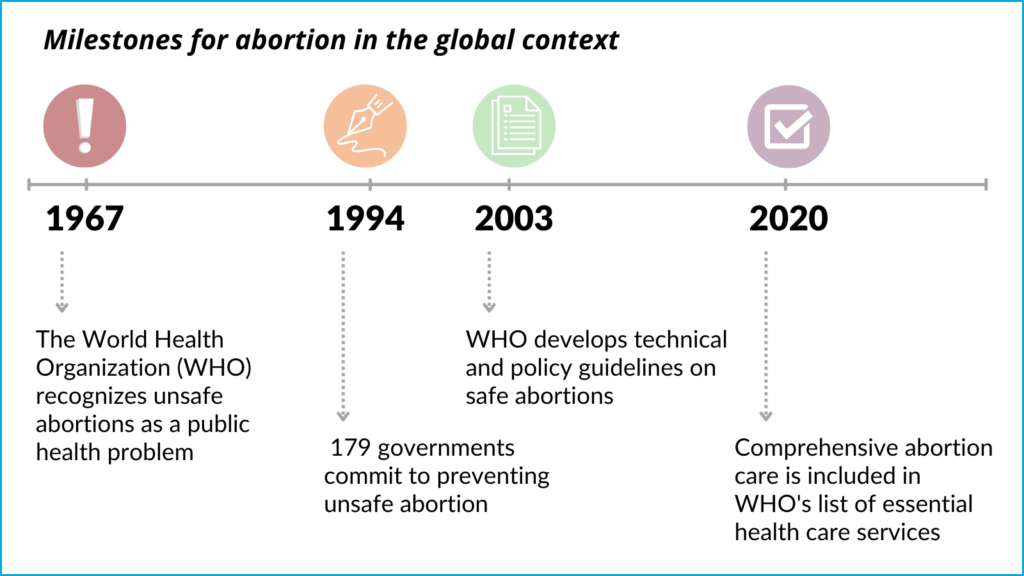

Each year, approximately seventy-three million abortions take place worldwide. Access to safe and legal abortion has been increasingly recognized as a fundamental human right. In 1994, at the International Conference on Population and Development, 179 governments signed a program of action that includes a commitment to prevent unsafe abortion.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized unsafe abortions as a public health problem earlier in 1967, and subsequently developed technical and policy guidelines on safe abortions in 2003. As of 2020, comprehensive abortion care is included in the list of essential health care services published by the WHO.

Significant progress has been made in global abortion policy in the last several decades indicating a growing global consensus that access to safe and legal abortion is both a human right and public health imperative. Over the last 25 years, at least 50 countries have liberalized their laws to improve access to abortion care and the majority of countries worldwide do not require parental authorization or notification for adolescents to access abortion services. However, 90 million birthing people of reproductive age still live in countries in which abortion is prohibited altogether. While most countries are taking steps to expand access and grounds for legal abortion, the US stands out with the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade and the enaction of more restrictive abortion policies that have followed.

Need for an enabling environment, especially for marginalized populations

An enabling regulatory and policy environment is crucial to ensuring that every birthing person has access to safe abortion care. Clear evidence shows that restrictions on access to safe abortion services do not reduce its incidence, but instead result in unsafe abortions and unwanted births. In fact, almost all deaths and morbidities from unsafe abortion occur in countries where abortion is severely restricted in law and/or in practice. The average rate of unsafe abortion is estimated to be more than four times higher in countries with more restrictive abortion laws than in countries with less restrictive laws. Additionally, abortion bans disproportionately harm historically marginalized people, including Black and Indigenous people and those from low-income communities.

Given the unique set of circumstances and constraints faced by adolescents, enabling laws and policies are even more crucial to support their reproductive health and rights. When accessing abortion services, adolescents face a range of barriers unique to their age group including cost, stigma, lack of confidentiality, misinformation, parental consent or notification laws, and judicial authorization requirements. Such legal requirements prevent adolescents from making autonomous decisions and make it more difficult for them to seek and access abortion care. In Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems, the WHO recognizes that abortion laws should include protections for informed and voluntary decision-making, autonomy in decision-making, non-discrimination, and confidentiality and privacy for all pregnant people, including adolescents. Additionally, according to this guidance, third-party authorization requirements hinder adolescents’ access to abortion, and increase the likelihood that they will seek unsafe abortions.

The average rate of unsafe abortion is estimated to be more than four times higher in countries with more restrictive abortion laws than in countries with less restrictive laws.

Before Roe was overturned, pregnant people under 18 seeking abortion care in the U.S. already had to navigate a series of legal and logistical hurdles to access appropriate care, and now, post Roe, these barriers have compounded and the process is even more difficult. However, there exists a vast network of activists, providers, and organizers helping pregnant youth access the care they need. While it is currently legal to travel out of state to obtain abortion care in the U.S., there is concern about child custody protection acts, which can criminalize transporting a minor across state lines to have an abortion without parental consent. While the Guttmacher Institute’s interactive map helps track the complex abortion policy landscape for each U.S. state, the Adolescent Atlas for Action (A3) Policy Checklist, created by the Population Council’s GIRL Center, maps national-level policies relevant to the lives of adolescents in 113 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including seven key abortion indicators.

What does the global abortion policy landscape look like?

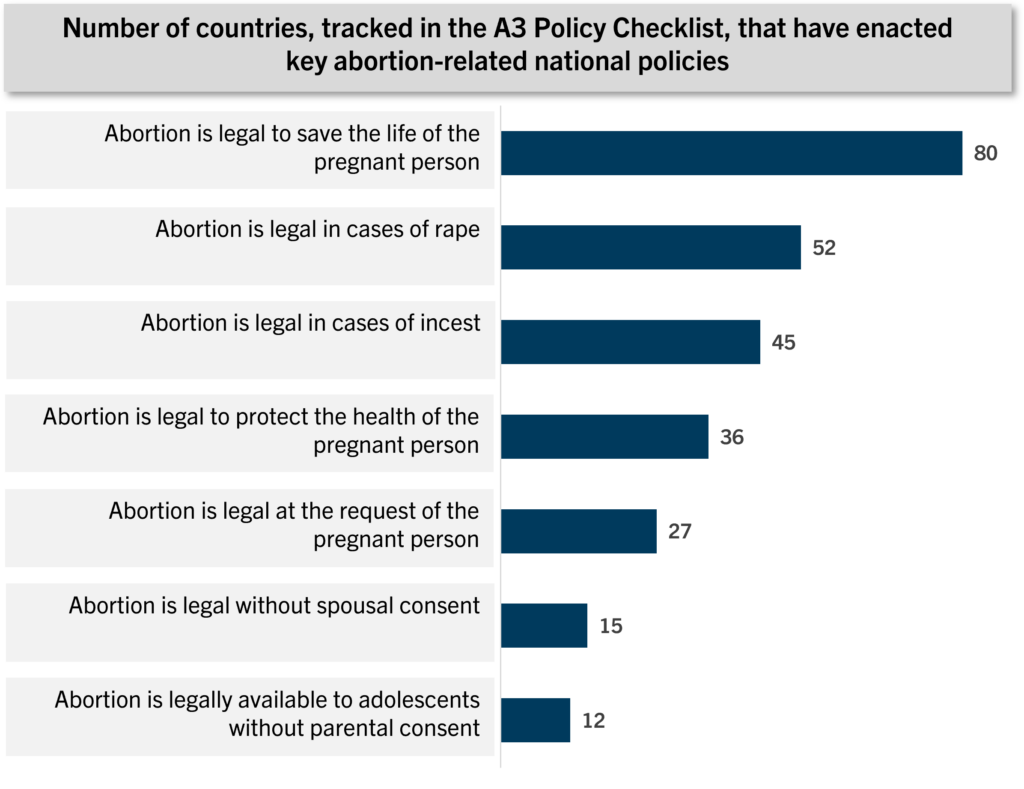

Almost 90% of countries globally allow abortion, at minimum, when the pregnant person’s life is at risk. Abortion is legal to save the life of the pregnant person in 71% of the 113 LMICs included in the A3. While it’s critical to allow abortion in situations where pregnancy poses a risk to a pregnant person’s life, only permitting abortion on this ground is insufficient for guaranteeing birthing people’s human rights.

Only 23% of LMICs (27 countries) have policies allowing legal abortion at the request of the pregnant person, despite the WHO’s guidance that this is the only legal ground which “recognizes the conditions for a woman’s free choice.” These barriers are amplified for adolescents, with only 11% of LMICs (12 countries) that have policies to ensure abortion is legally available to adolescents without parental consent. Such restrictions prevent adolescents from making autonomous decisions and can inhibit them from seeking safe abortion care.

Looking ahead

Over the past several decades, incremental and transformative progress in securing legal rights and access to abortion has been made globally. Maintaining this momentum towards liberalizing abortion laws and creating enabling legal and policy environments is critical to ensuring reproductive rights and autonomy, particularly in light of the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade. It’s imperative that countries continue to enact evidence-based policies to support sexual and reproductive health, rights, and autonomy that strive to make abortion available upon request of the pregnant person and make such care universally affordable and accessible. Abortion laws and policies should pay particular attention to adolescents and prioritize their autonomy and access to safe abortion care.